https://pagead2.googlesyndication.com/pagead/js/adsbygoogle.js?client=ca-pub-4000887400212447

The creative partnership between Tracey Emin and Sarah Lucas reached its most intense and influential point during the mid-1990s, around the time they ran The Shop in Shoreditch, East London. Though open for just six months, The Shop has since become one of the most iconic moments in late twentieth-century British art, widely recognised as a catalyst for both artists’ careers and for the wider Young British Artists (YBA) movement.

Do you love contemporary art and want to discover more of what the capital has to offer? Book onto the Tate Modern Official Discovery Tour and explore the world of the Young British Artists.

Official Discovery Tour

The Shop: A Turning Point in British Art

Emin and Lucas opened The Shop as a way to sell their own artwork directly to the public. Operating on a limited budget and with few resources, they produced all the stock themselves—often at speed and under pressure. Remarkably, everything sold on the opening night, forcing them to create more work immediately. What began as a practical solution quickly evolved into a cultural phenomenon.

Located in Shoreditch at a time when East London nightlife largely shut down by 11pm, The Shop became a hub for late-night drinking, conversation, and artistic exchange. The space blurred the boundaries between art, commerce, and social life, cementing its reputation as the place to be in the mid-90s art scene. Both artists later referenced the relentless chain-smoking and intensity of those six months as emblematic of the era.

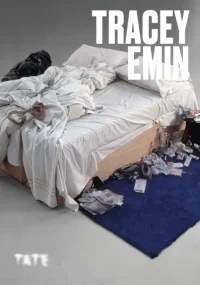

Artists Series: Tracey Emin, the latest publication, will be released at the end of February 2026 and is now available for pre-order.

The Final Night and a Defining Gesture

The final night of The Shop coincided with Tracey Emin’s 30th birthday, marking a symbolic end to the collaboration. For the closing event, Emin and Lucas produced a series of badges together, featuring imagery ranging from comic innuendo to themes of aggression and violence.

Emin’s final act was characteristically uncompromising: any unsold artwork was cremated, with the ashes forming the final piece, titled The Shop. This gesture—destructive, performative, and deeply personal—has since been interpreted as both an ending and a statement about value, authorship, and ephemerality in contemporary art.

Feminism, Confession, and Subversion

Despite their distinct artistic voices, there are clear thematic overlaps in Emin and Lucas’s work both before and after The Shop. Both artists have been described—sometimes dismissively—as the “Bad Girls of British Art”, yet this label also situates them as key figures within third-wave feminism.

In works such as Au Naturel, Lucas employs torn mattresses, stained fabrics, and crude symbolism—such as a bucket suggesting female genitalia—to confront how women’s bodies and sexuality are framed. While Emin’s practice is rooted in confession, Lucas’s is sharper, cooler, and more confrontational, yet both challenge patriarchal expectations of female artists.

Lucas has referred to Emin’s work as “cheap,” not as an insult but as a commentary on its confessional openness, particularly around sexual vulnerability and dissatisfaction. Emin’s work often exposes private experience, emotion, and trauma, while Lucas tends toward subversion, using everyday objects to dismantle gender stereotypes.

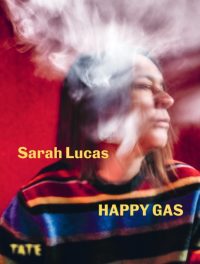

Happy Gas explores Sarah Lucas’s work in greater depth, examining how her use of ordinary objects in unexpected ways has consistently challenged ideas of sex, class, and gender over the past four decades.

Friendship, Love, and Misinterpretation

The closeness of Emin and Lucas during The Shop period has frequently led to speculation about a sexual relationship, particularly due to photographs showing them dressed similarly—bleached denim, shirts, peace signs—projecting a sense of unity and intimacy.

Lucas once stated:

“We were quite in love with each other at first—we bought a beach hut together—but it was quite difficult working out what to do with that love, so for about two months we didn’t talk to each other because it was too difficult.”

While often cited as evidence of a romantic relationship, this statement more convincingly points to a deep friendship complicated by emotional intensity and creative proximity.

Gender, Power, and Artistic “Otherness”

Art historian Linda Nochlin famously argued that women’s art has historically been framed as “the other,” marginalised by patriarchal institutions that expect a domestic or decorative femininity. Women artists who resist this are often labelled deviant, unfeminine, or abnormal.

This framework helps explain why Emin and Lucas’s work—particularly its focus on sexual dissatisfaction, aggression, and bodily autonomy—has so often prompted intrusive speculation about their sexuality. The discomfort lies not in the work itself, but in how male-dominated structures respond to women who refuse to aestheticize desire or conform to traditional narratives.

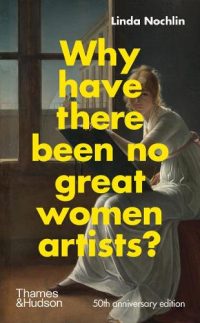

Want to explore Linda Nochlin’s groundbreaking ideas on women and art? Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?, the 50th Anniversary Edition, is now available in hardback.

A Lasting Influence

More than three decades on, The Shop stands as a defining moment in British art history. It represents a raw, uncompromising collaboration that challenged ideas of value, gender, authorship, and intimacy—both personal and artistic. Tracey Emin and Sarah Lucas didn’t just sell art from a shop; they reshaped how art could be lived, shared, and contested.

This article contains affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission if you click through and make a purchase — at no extra cost to you.

Leave a comment